|

The Australia-China Chamber of Commerce and Industry of New South Wales |

||||

|

|

|

|||

|

|

LAW ENFORCEMENT IN CHINA For the International Seminar on the Environment of Law Enforcement

Supervision 27-29 June 2000 Mianyang City, Sichuan Province Submitted by: The Australia-China Chamber of Commerce and Industry of

New South Wales Written by: John Zerby, Vice President of the Australia-China Chamber

of Commerce and Industry of New South Wales and John Yuhong Wang, Chief Representative, Beijing, of the

Australia-China Chamber of Commerce and Industry of New South Wales |

|||

|

|

The Australia-China Chamber of

Commerce and Industry of New South (which is more easily abbreviated as

ACCCI, or the “Chamber”) is grateful for the invitation to participate in this

international seminar on the environment of law enforcement supervision in

China. Our objective is to contribute

some thoughts to the issues that comprise the theme of the seminar and to

offer our support for the continuing discussion of these issues. ACCCI was established in Sydney

on 16 September 1976. Its purpose is

to foster two-way trade, commerce, industry, investment and cultural

relations between the two countries.

Since the first years following the establishment of diplomatic

relations with China in 1972, two-way trade grew from A$158 million to A$10.7

billion in 1999. With Australia's

population of 19.1 million, this is equivalent to A$560 (US$340) per

person. That amount is only slightly

less than for the two-way trade between China and the United States, which

was US$346 per person in the U. S. in 1999.1 Australia has traditionally been

an important supplier of the industrial raw materials and foodstuffs China

needs for its modernisation. About 61

per cent of Australian merchandise exports to China are primary products and

consist principally wool, wheat, sugar, barley, cotton, iron ore, alumina and

coal. In recent years, there has been

an increase in manufactured exports such as electrical machinery and appliances

and telecommunications equipment.

Exports of services, especially from Australian banks, law firms and

insurance companies are also increasing.2 These trends, as well as the

growing evidence of economic complementarities between Australia and China, are certain to increase with

continued restructuring of the Chinese economy. Participation in this important discussion is therefore

consistent with the Chamber's objective of fostering two-way trade and

investment. |

|||

|

|

The preparation of this paper

illustrates the nature of the partnerships that the Chamber has

fostered. John Zerby, who is vice

president of ACCCI, is an academic economist specialising in various development

issues of the East Asian economies, including the Chinese economy. His contribution to this paper is in

proposing a framework for reform of law enforcement supervision. John Yuhong Wang, chief

representative of ACCCI in Beijing, is a partner in a law firm in

Beijing. He has law degrees from the

University of Beijing as well as the University of Sydney. He is a business migration agent for

Australia and also specialises in company law in China. His contribution to this paper is in

adding a more detailed discussion of China’s legal issues, including

administrative enforcement of NPC laws. |

|||

|

|

Following the World Bank's

definitions, we use the word “state” to refer to the set of institutions that

possess the means of legitimate coercion that is exercised over a defined

territory and its population.3 Although the word “government” is sometimes used in a more

restrictive way in referring to the people who occupy positions of authority,

we use the two words interchangeably. The public sector consists of

all people who are employed by the state and whose main income is derived

from public funds. These funds

consist of tax revenues as well as income accruing to the state from

government enterprises. The public

sector does not include employees of enterprises which may be partly or fully

owned by the state but whose managerial decisions are made independently of

the state. A main function of the state is

to assist in satisfying the economic and social needs of the people within

its territory.4

This is generally achieved through two separate but related

activities. The first is establishing

a set of rules that authorise and regulate the behaviour of all participants

in the economic and social processes.

The second is the implementation of these rules in an efficient and

effective way. The portion of the public sector

that sets the rules includes legislative authorities, such as national and

sub-national people's congresses, as well as senior administrative personnel

who have been delegated the authority to set rules and regulations. The tasks of this portion of the public

sector are (1) to accurately assess the economic and social needs of the

population and (2) to establish rules and regulations that are effective in

achieving those needs. The portion of the public sector

that implements the rules and regulations is sometimes referred to as the

operational component of the state apparatus. Although these groups or agencies within the government take

instructions from the authorising and regulatory authorities, considerable

discretion typically occurs in the way, and in the speed, with which the instructions

are followed. Perhaps of greater

importance, the capacity of this portion of the public sector to implement

the rules and regulations is a critical element in the success of both

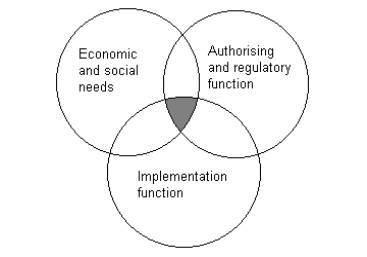

portions of the state apparatus. A simple diagram can be used to

show the relationship between these functions 5 (Fig

1). The nation's economic and social

needs are represented within the circle on the left-hand side. The circle on the right-hand side

represents the authorising and regulatory function of the state. The relatively small overlap with the two

circles indicates that the state is directly concerned with a correspondingly

small portion of the nation's economic and social needs. The remaining needs are supplied without

assistance from the state. Fig. 1. Pubic sector functions

and economic and social needs.

The third circle represents the

implementation function of the public sector and its overlap with the other

two circles (the shaded area) shows the portion of the nation's economic and

social needs that are successfully met with both authorisation and

implementation. The efficiency and

effectiveness of the public sector can therefore be assessed by the size of

the shaded area relative to the resource costs associated with the two

functions. Prior to the beginning of

economic reform in China in 1979, large portions of the nation's economic and

social needs were supplied directly by the state. This resulted from the fact that the state was the only

effective supplier. Authorisation and

implementation were closely related through central planning, and rules

consisted mainly of output targets combined with input quotas. Despite a relatively large

shaded area in relation to public sector functions under the pre-reform

arrangement, the economic costs were large and increased over time. This was due mainly to the difficulty in

matching output targets with the economic needs of the nation (mismatch

between supply and demand). The

arrangement also limited technological development since this cannot be

effectively entered into a central plan. Economic reform was initiated

for the purpose of allowing markets to develop in China and through this

development to correct the mismatches between supply and demand. The “open door” policy served the

important function of allowing a greater amount of technology transfer. The overwhelming success of these early

reforms (in the 1980s) resulted in a rightward movement of the authorising

and regulatory circle in Fig. 1, as a greater proportion of economic and

social needs were supplied without direct involvement of the state. The implementation circle also

shifted downward with increased progress in economic reform. The reasons can be traced to (1)

uncertainty about authorisation and regulation with the discontinuation of a

central plan, and (2) increased complexities arising from a mixture of market

outcomes and regulatory outcomes. China's three-tiered system of

authorisation and implementation also contributed to greater implementation

difficulties. The central government

was the first to withdraw from direct involvement and delegated much of the

economic decision-making to lower levels of government. Some implementation functions were

therefore either partly or fully duplicated within the various levels. This decentralisation was an

essential element in breaking away from central planning. It also conveyed the general belief that

lower levels of government are more aware of the economic and social needs of

the people within their respective territories. Additionally, being closer to local markets, lower levels of

government were expected to have a greater capacity to assist in adjusting

local supplies to those markets. The success of the initial

reforms can be attributed more to the incentives built into the reforms than

to the capacity of the public sector to implement them. For example, the family responsibility

system assured rural families of greater income through increases in state

procurement prices and a capacity for sideline products that could be sold on

the open market. The desire to

sustain this higher income gave rise to improvements in production methods. Similarly, allowing state-owned

enterprises to sell over-quota production on the open market, and to retain a

large portion of the proceeds of those sales, created a strong incentive to

comply with the industrial reforms.

As well, fiscal responsibility on the part of lower levels of

government in China was encouraged through a system that allowed a greater

portion of additional revenue to be retained at the lower levels. During the 1990s, financial

incentives for compliance with continuing reforms became more difficult to

achieve. For example, many township

and village enterprises could not afford the cost of complying with environmental

regulations and were forced to close down.

Similarly, many state-owned

industrial enterprises continued to incur debt as a result of lower profits

with market-priced inputs and greater competition in their major output

markets. The capacity of many of these

traditional enterprises to initiate new products (or new production methods)

was limited by their existing indebtedness.

Their ability to reduce costs was restricted by the social obligations

that were carried over from the earlier industrial system. Perhaps of greater importance to

the continuing success of economic reform in China, as the market system

became a more controlling element in the price and quantity of most outputs,

markets became more interdependent.

For example, fewer employment opportunities with township and village

enterprises added to the desire for rural-to-urban migration and this

increased the need for more urban infrastructure. New (or different) economic and

social needs were therefore created by the market economy. Although some of these were predictable,

the time necessary for authorisation was in some cases substantial,

especially if a new law required old laws to be amended (or if a new law

enacted by an upper-level government conflicted with those of a lower-level government). Similarly, with increased trade among

neighbouring provinces, implementation of an authorisation or regulation by

one provincial government often conflicted with similar implementation for

another provincial government. To summarise the role of the

state in economic activities in China, during the 1980s the authorisation and

regulatory function of the state focused on creating an environment within

which the regulation of economic activities would become more market

oriented. The implementation function

followed the principles that were established for a more open and a more

decentralised system. Public sector personnel at

provincial and municipal/county levels became more involved in promotional

activities. These functions are

generally regarded as being successful, although, as noted above,

implementation costs may have increased through a duplication of efforts

among the various levels of government. During the early 1990s, the

authorisation and regulatory function of the state began to focus on

administrative adjustments that were necessary to maintain macroeconomic

stability. Inflationary pressures

occupied much of the attention of administrators and rising unemployment

following cut-backs in state-owned enterprises became a major issue in the

first half of that decade. The East Asian crisis that began

in 1997 highlighted weaknesses in regional financial systems and motivated a

number of authorising and regulatory initiatives of the central government in

China. A new securities law, a reorganisation

of the People's Bank of China and supervisory committees for the large state

banks were important outcomes of these efforts. Implementation of these new laws

was apparently easier with the creation of new institutional

arrangements. For example, the China

Securities Regulatory Commission that was formed in 1992 is implementing the

securities law. New regional offices

of the People's Bank of China were created and the Product Quality Law

established a new group of inspectors who issue public warnings for

non-compliance. Little occurred during the 1990s

to foster a re-orientation of the public sector, especially with lower levels

of government, to increase their capacity to implement continuing

administrative adjustments. We focus on

this aspect from the remainder of the discussion. |

|||

|

|

The judicial system in most

countries has both an interpretative function and an enforcement

function. These functions are

sometimes difficult to separate and therefore do not fit easily into the

simplified scheme shown in Fig. 1.

Nevertheless, there is a connection. While the interpretative

function of the judicial system has an impact on the content and application

of rules that are established by the authorising and regulatory function of

the state, the judiciary depends upon a prior authorisation through which the

relevant law was initiated. The

interpretative function is therefore a form of implementation. In China this is clearly distinguished

with an interpretative function given to the Standing Committee of the

National People’s Congress.6 As a dispute resolution

procedure the judicial system operates in a manner that is similar to a range

of informal resolution schemes within the public sector. Additionally, as an instrument for

enforcing law, the judicial system is closely related to major industry

“watchdogs” that are part of the state apparatus. A recent report by the

Australian Law Reform Commission, entitled, Managing Justice: A Review of the Federal Civil Justice System 7 recognised this connection. The Commission recommended that empirical

studies be made of the quality and effectiveness of all such dispute resolution

and “watchdog” schemes with a view to determining their ultimate impact on

the workloads of courts and tribunals. We suggest that this connection

justifies a broadly based framework within which the capability of law

enforcement supervision can be made.

A framework is concerned with a coherent set of ideas for influencing

and initiating action. A framework

does not necessarily emerge fully developed.

It may evolve over a period of time; but it must have at any given

time a series of component-ideas that can be used as reference points in the

evolutionary process. We are aware that reforms in

China have generally been made in a step-by-step manner, rather than

instituting a single, comprehensive program that includes a range of reforms affecting

most aspects of public sector functions.

The choice made by China has proved to be successful in creating

durable outcomes.8

We nevertheless suggest that the connection between enforcement of

Forestry Law and Environmental Protection Law with other types of

enforcement, and with other public sector functions, requires that some

attention be given to a broadly based framework. |

|||

|

|

Australia is frequently

mentioned by the World Bank and the International Monetary Fund as an example

of public sector reforms that were aimed at making the functions of

government more transparent, competitive and results-oriented. Although these objectives apply to most

countries, the manner in which the reforms are instituted will necessarily

differ as a result of many social, cultural and historical factors. We do not suggest that

Australia's public sector is or should be a “model” for China's public

sector. Nevertheless, some of the

ways in which public sector institutions were strengthened in Australia are

worthy of consideration. A major

objective of this seminar is to learn from the experience of other countries,

and that is frequently more effective if it is built up in a case-by-case

manner. Written Comments about Policies

from the Public Sector During the 1980s, the central

government in Australia initiated the practice of requiring written comments

from various ministries and agencies on the proposals for new policies (or

policy changes) from other ministries and agencies. This accomplished two objectives. First, in order to issue

constructive comments, it was necessary for the various ministries and

agencies to acquire some of the knowledge that was previously reserved for

one ministry or agency. This

increased the degree of flexibility in the public sector and enabled

transfers of personnel from one ministry to another to be made more easily. Second, the comments gave an

indication of implementation capability.

This, in turn, led to changes in the authorisation or regulation for

the purpose of tailoring it to suit the capability. It also highlighted areas where improvements in capability were

required. Success depended upon adherence

to a fairly rigid timetable in order to avoid long delays in the policy

planning stage. Not all ministries

and agencies viewed the task of commenting on the activities of other

ministries with equal seriousness, but generally those with interests similar

to those contained in a proposal accepted the task as an important part of

their own work plan. The desire to

gain a better understanding of the work plans of similar ministries became

part of their medium-term institutional strategies. In applying this to China, we

note that discussions frequently occur among representatives of various

ministries, departments and offices.

However, most of these discussions are organised to suit particular

issues and are arranged as a special occasion, such as this seminar. These discussions and seminars are of

course important and should be continued.

We recommend that a procedure be established for regular and more

continuous exchanges of opinion about the tasks and work plans of the public

sector organisations that are represented here today. Cost of New Proposals Balanced

Against Offsetting Savings The principal objective of

public sector reform in Australia was to allow changes in policies to occur

without adding increasingly larger amounts to government spending. During the 1970s and early 1980s, non-government

organisations called attention to the apparent desire of some ministries and

agencies to increase their size, and therefore their influence within the

public sector, by proposing an ever-expanding range of new policies and

programs. Other ministries and

agencies then followed in the same manner and this added substantially to the

size of government. Similar experiences occurred in

other countries in relation to government regulations. Increased complexity in the regulatory

process not only added to the cost of doing business, for those enterprises

that were being regulated, but it also increased the number of personnel

employed by the regulators. This was

one of the most pressing arguments that led to a general downsizing of the

public sector in most countries. The need to find offsetting

savings also encouraged innovations in administrative procedures. Non-government people cannot evaluate

government administration easily or quickly (though they may have useful

input for improving the procedures).

Public sector innovations are more easily obtained from within the

public sector, but some form of incentive is generally necessary to stimulate

the innovative process. In relation to Forestry Law and

Environmental Law, cost savings arise mainly from the capacity to prevent

severe damage to forests and to the environment. While the cost of this damage is difficult to connect directly

to compliance with a specific forestry or environmental laws, it is important

to initiate the thought process that evaluates of the benefits of enforcement

and compliance, relative to the costs of achieving the enforcement and

compliance. On the issue of measurement, the

World Bank, Asian Development Bank and most bilateral aid agencies in OECD

countries have evolved a process for benefit-cost analysis that can be

applied to individual projects. We

have had some experience with this type of analysis and recognise that the

quantitative procedures generally lack precision. However, the important contribution that stems from the

analysis, is not the final figure, but rather the systematic procedure of

collecting (listing) the various costs and the benefits. We recommend that supervisory personnel in China’s regulatory

divisions give greater attention to measures of the costs and benefits of law

enforcement and use these measures to develop a comprehensive work plan. Measuring Public Sector

Performance From Outcomes The public sector at the central

government level in Australia is almost fully oriented toward performance

based upon results or outcomes. The

preference for “outcomes” rather than “outputs” is difficult to trace, but

seems to have developed from limitations associated with measuring physical

units of outputs.9 Perhaps the most common use of

“outcome” is in relation to a policy or plan, and is frequently linked to the

stated objectives of a specific activity.

We use, for purposes of illustration, the objectives of this seminar: It is the aim of this

international seminar to organise the experts from home and abroad to

exchange views on the issues of legal enforcement supervision, to pass on the

successful practices and experiences of overseas legal supervision machinery,

and to learn from the foreign experience so as to benefit the construction of

our own legal supervision environment. A likely outcome of the seminar

is a list of priorities that will subsequently be examined by the

participating public sector agencies for the purpose of initiating reforms in

the way they supervise the enforcement of relevant laws and regulations. It might appear that an

“outcome” is a mere restatement of the objectives, but it does more than

that. In order to add value, the restatement

must be put in such a way that it can be confirmed later as a specific result

(or set of results) of the activity.

This gives rise to two benefits.

First, it focuses attention during the activity on what is to be

achieved. In that sense, it helps to

avoid wasted or ineffective effort.

Second, it provides a convenient basis to assessing whether the time,

effort and expense that went into the activity can be justified. Applying this to enforcement of

environmental laws, outcomes should extend beyond a “target output” of

inspecting a fixed number of factories for emission standards or imposing a

specific number of fines. Enforcement

outcomes should include a realistic target for environmental improvements,

together with a human resources plan to achieve those targets. We recommend that enforcement supervision in China adopt a “outcomes

approach” that links feasible and realistic implementation objectives to

human resource requirements. These outcomes should be stated

in such a way that they can be subsequently confirmed in relation to both the

input of resources as well as the implementation output, with due

consideration given to qualitative factors. Educating Enforcement Officials The Australian Law Reform

Commission (reference given in note 6) made a strong case for improvements in

education, training and accountability for the entire legal profession. Emphasis was placed on traditional members

of the profession (lawyers, judges and members of tribunals), but a similar

statement could be made that includes public sector personnel engaged in

enforcement activities. Education, training and

accountability are of utmost importance in getting the supervisory structures

right, achieving reform within the entire system and maintaining high standards

of performance. A healthy

professional culture requires lifelong learning and takes ethical concerns

seriously. The Commission also found that a

training program for professional skills that is properly conceived and

executed should not be a narrow technical or vocational exercise. Rather, it should be fully based upon an

appropriate mixture of theory and practice, devoted to the refinement of the

high order intellectual skills, and calculated to create a sense of ethical

propriety, as well as and professional and social responsibility.10 Professional practitioners in

Australia were queried to determine the type of skills that were missing from

their basic education. Communication

skills were identified most frequently.

Skills of critical appraisal of information and research, including

statistics, were also mentioned. We recommend that the educational requirements for law enforcement

supervisors and officials be comprehensively studied in China for the purpose

of designing a professional training program that would contribute to the

achievement of specific objectives. These objectives should include:

(a) adopting the right supervisory structures, (b) achieving reform within

the entire enforcement system, and (c) maintaining high standards of

performance. Improving

Intergovernmental Relations in China We believe that the

administrative system linking the three levels of government will be placed

under increasing pressure as a result of the competing needs of smaller jurisdictions.

The new Legislation Law, which was adopted on 15 March 2000 and will become

effective on 1 July 2000, will help to avoid, and hopefully eliminate, the

conflicts and inconsistencies between national laws and laws of lower-level

governments. We note that the new law

clarifies the separation of law-making authority among the three levels in

China, and in doing so it conveys elements of a federal system of

government. Perhaps more importantly

for supervision of law enforcement, the new law requires lower-level

governments to amend or repeal, on a timely basis, any decree or provision

that contravenes a national law or administrative regulation.11 Specific authority is given to

higher-levels of government in China to review and approve local decrees

before they are implemented.12 Authority is also given to higher-level governments to amend or

cancel existing decrees or administrative rules or local rules that are

considered to be inappropriate.13 Enforcement of any such

amendments or cancellations is nevertheless a major concern. Provincial governors and mayors of

municipal governments will be assessed mainly on their contributions in their

own jurisdictions, and compliance with higher-level laws may not receive

priority treatment by the lower-level public sector. Lower level governments will

need to know why their legislation must be changed and may need to be

convinced that the national laws and regulations are better then their local

laws and regulations. Regular

briefings by the higher-level government may accomplish part of this

objective, but we think that may not be enough. Lower level governments are

likely to require technical assistance to guide them in the necessary

compliance and in enforcing the resulting laws and regulations. We can suggest that the procedures adopted

by the World Bank and the Asian Development Bank in giving technical

assistance to borrowing countries, so that they may more easily comply with

the respective bank’s requirements, could serve as a model. Bank staff or external

consultants are assigned to the appropriate ministry for designated periods

of time. The type of assistance

required is generally determined by negotiation between the bank and the

relevant ministry. Personnel assigned

to the technical assistant tasks are given specific instructions and their

work is carefully monitored. We recommend that technical assistance be provided to lower-level

governments by higher-level governments for improved supervision of specific

laws and regulations that follow from the authorisation and regulatory

function of the higher-level governments. We believe that this will build

stronger institutional arrangements between central ministries and

counterpart departments in the lower-level governments. It will also lead to a transfer of

knowledge and experience that will enhance capability at all levels. We suggest that a stronger institutional

linkage will become increasingly more important as China develops more fully

its “rule by law”. |

|||

|

|

The suggestion of an Australian

Academy of Law was made by the Australian Law Reform Commission (in paragraph

2.115 of the reference cited at note 7).

The proposed academy would have an institutional standing that is

approximately that of the Academy of the Social Sciences in Australia (ASSA),

the Australian Academy of Humanities (AAH) and the Australian Academy of

Science (AAS). A similar suggestion could be

made for a Chinese Academy of Law.

Such an organisation could draw together the various strands of the

legal system to facilitate effective intellectual interchange through

discussion and research in areas of concern.

It could nurture coalitions of interest and could have a special focus

on issues of professionalism (including ethics) and on education and

training. Since such an academy is only

now being proposed in Australia, we cannot give you an account of Australian

experiences. We note, however, from

the comments of the Australian Law Reform Commission, that the Singapore

Academy of Law and the American Law Institute comprise similar bodies. We suggest that a Chinese

Academy of Law could give increased status and recognition within China to

the “rule of law”. This would greatly

assist the task of law enforcement and would also allow on-going linkages

with similar academies in other countries. The need for such on-going

linkages will become more important when China becomes a member of the World

Trade Organisation. Trade disputes

often arise as a result of incomplete information about the way one nation

makes and enforces trade laws in a "uniform, impartial and

reasonable" manner. Information that is not

up-to-date creates misunderstandings about enforcement of laws. For example, a recent opinion by Stanley

Lubman of the Stanford Law School stated: In addition, [China] should

provide for procedures to challenge legislation, both prospective and already

in effect. This would be an

innovation, because under current Chinese practice, administrative agencies

can be challenged by affected persons or organisations if they allegedly

misapply laws in specific cases; but general rules cannot be challenged as

illegal or as conflicting with other laws or regulations. China should commit to repair this

omission.14 This has now been changed by the

Legislation Law mentioned earlier,15 but a delay in

recognising that change focuses attention on what has already been done and

therefore creates an erroneous impression of the tasks remaining. A timely exchange of information is of

vital importance in preventing conflicts, and a highly regarded organisation

is required for the purpose exchanging that information. Need

for Incentives We mentioned in an earlier

section that economic reform during the 1980s proceeded well because of the

financial incentives that were built into the reforms. Subsequent reforms were more difficult

mainly because they lacked corresponding financial incentives. Success in reforming the

environment for law enforcement supervision in China, and in reforming other

aspects of the legal system, will require other incentives to be created. As the reform process expands it will also

be necessary to neutralise disincentives. It is generally easier to

prescribe the necessary ingredients of the reform process than to create the

incentives. From the economic point

of view, the cost of the incentives must not be greater than the benefits

that are expected to arise from the reform.

This is even more difficult to determine. Whether the reform process is

step-by-step or comprehensive, it is necessary to pause periodically to

ensure that the costs are not exceeding the benefits. The decision-making process is likely to

be easier for forestry and environmental protection since the residents of

the community will have visible evidence of the benefit. They must nevertheless be convinced that

the process will achieve visible benefits before they, as individuals,

willingly comply with laws and regulations. Some environmentalists have

suggested that sustainable development begins with individuals who volunteer

to restrict their behaviour, based mainly on faith that others will do the

same. Less faith is required as the

numbers build to the point at which visible benefits appear, but it is then

more difficult to prevent individuals from refusing to comply since they view

their individual actions as insignificant to the continued improvements. This means that the environment

for law enforcement supervision must continuously re-invent itself and change

to suit changing circumstances. It is

nevertheless important to get the right structure with each change, since

otherwise the tasks of achieving compliance will be increasingly more

difficult. We hope some of the suggestions

we made will help to focus attention on obtaining the “right structure”. We cannot state what the structure should

be, since it must inevitably have characteristics that suit China’s specific

law enforcement needs. Seminars such

as this one are important steps in achieving that outcome. |

|||

|

|

|

|||

|

|

1. Australia's exports to China in 1999 were $A4,084

million and imports were A$6,578 (Australian Department of Foreign Affairs

and Trade). U. S. exports to China in

1999 were US$13,118 million and imports were US$81,786 (U.S. Census, Foreign

Trade Division). The population of

the U. S. is 274.6 million. The current

exchange rate of US$0.6071 per Australian dollar was applied. 2. Australian Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade,

“People's Republic of China, Trade and Investment”, from Country/Economic

Information at Internet site: http://www.dfat.gov.au. 3. World Bank, The State in a Changing World, World

Development Report 1997, p 20. 4. Traditionally, the state is

said to have certain “core” functions including national defence, ensuring

the security of persons and property, educating the citizenry and enforcing

contracts. See World

Bank (note 3), p. 20. On this basis,

other functions are “non-core” and need not be supplied entirely or directly

by the state. These other functions

should nevertheless contribute in a measurable way to satisfying social and

economic needs, and the state has the responsibility of ensuring that

adequate supplies are available. 5. The diagram is a variation of one used by Anwar

Shan, “Balance, Accountability and Responsiveness: Lessons About

Decentralisation”, World Bank Policy Research Working Paper No. 2021. 6. Refer to Section Four

(Article 42) of The Legislation Law of the People’s

Republic of China. 7. Available at: http://www.austlii.edu.au/au/other/alrc/publications/reports/89/. 8. In comparison, public sector

reforms that are undertaken on a comprehensive basis often require frequent adjustments

or “fine tuning” to suit particular situations. See Michele de Laine, “International Themes in Public Service

Reform”, Background Paper 3, 1997-98, Parliament of

Australia, Parliamentary Library, 22 September 1997. 9. A number of published discussions

relating to the undesirable features of reliance upon physical output as a

measure of performance can be found, but several such

features that are mentioned by Michele de Laine (op. cit. at note 7) are

particularly good. 10. Australian Law Reform Commission,

op. cit. (at note 6), paragraph 2.85. 11. Stated in Article 64 of The Legislation Law of the People’s Republic of China. 12. Stated in

Article 63 of The Legislation Law of the People’s Republic of China. 13. Stated in Article 88 of The Legislation Law of the People’s Republic of China. 14. “China's Accession to the WTO: Unfinished Business

in Geneva”, by Stanley Lubman, dated 6 May 2000 in ChinaOnline

[http://www.chinaonline.com]. 15. Article 90 of the Legislation

Law states: “Where any state organ and social group, enterprise or

non-enterprise institution or citizen other than the bodies

enumerated above, deem that an administrative regulation, local decree,

autonomous decree or special decree contravenes the Constitution or a

national law, it may make a written proposal to the Standing Committee of the

National People’s Congress for review, and the office of operation of the

Standing Committee shall study such proposal, and where necessary, it shall distribute

such proposal to the relevant special committees for review and

comments.” The translation was by

John Jiang and is published in ChinaOnline [http://www.chinaonline.com]. Return to the top of this page. |